Colonial New England’s beverage past gets a new look

By Liz Boardman

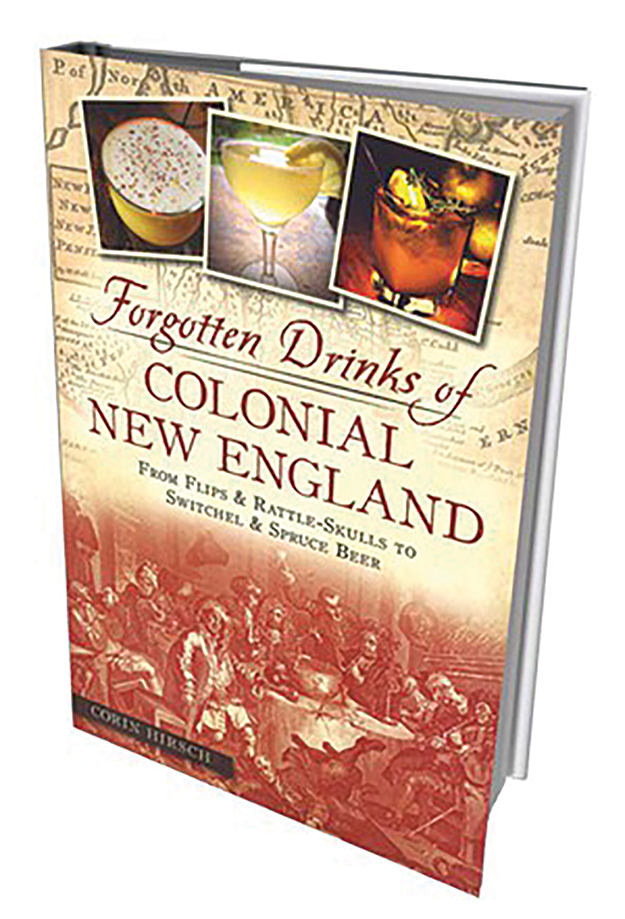

Forgotten Drinks of Colonial New England: From Flips and Rattle-Skulls to Switchel and Spruce Beer by Corin Hirsch, American Palate/the History Press, 144 pages.

Grog and flip the hot drinks of 2014? Everything old is new again and Corin Hirsch, author of “Forgotten Drinks of Colonial New England: From Flips and Rattle-Skulls to Switchel and Spruce Beer,” thinks a look at history might bring those, and other colonial drinks, back in style.

In her book, Hirsch takes an in-depth look at the ale, beer, wine, cider and spirits of our forefathers, a group that imbibed heartily, and not only because the water supply wasn’t safe. Colonists also drank for enjoyment, nutrition and for the local economy. Taverns, she writes, were also mandated in many new towns in 1600s Massachusetts and Connecticut, as the centers of community.

And what was served, in many cases, is familiar: ale and beer, wine, brandy, rum and whiskey. At least two others, mead and cider, have made a comeback in recent years. Hirsch’s research included exploring and making such colonial draughts and cocktails as the Rattle-Skull, described as a potent mix of seasoned porter, rum, brandy and sherry, and the variety of drinks called flips, which included eggs as much as for protein as presumably for taste.

“A flip was a blend of beer, rum; a sweetener such as molasses, sugar or dried pumpkin; and occasionally eggs and cream,” Hirsch writes in her book. The ingredients were mixed in a pitcher, sprinkled with nutmeg and heated. For the finishing touch, a hot fire poker (a flip dog) was plunged into the center of the drink, whipping it into a froth while adding an earthy flavor. “It sounds disgusting,” Hirsch said, “But in doing informal tastings, that’s the one people enjoyed.”

Grog is also ripe for a comeback, she predicted. It is two parts water to one part rum, with citrus juice and a sweetener. The citrus fruit “masked foul water or rum” and delivered vitamin C, helping to stave off scurvy, Hirsch said. “It’s a simple blend of rum, water, lime, sugar and spice, and is quite delicious,” she added.

Modern Day Inspiration for Sons of Liberty

It turns out Hirsch isn’t the only one looking back to the past for new inspiration. Michael Reppucci, owner of Sons of Liberty Spirits Company in Peace Dale, Rhode Island, introduced hop-flavored whiskey in May, after being inspired at the distillery at Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home in Virginia.

Reppucci’s mentor, Master Distiller Dave Pickerell, formerly of Maker’s Mark, now works with Mount Vernon, where the first president’s distillery has been restored to demonstrate 18th century distilling from seed to barrel.

“George Washington was the largest whiskey distiller of that time, and when they rebuilt at Mount Vernon, they traced the original recipe,” Reppucci said. “And they used hops.” Reppucci explained that Washington’s recipe boils water with hops as a first step, because it helped with sanitation.

Reppucci often says that whiskey is a form of aged beer, but even so, the idea of a hops whiskey seemed “avant garde” to him. But just as there are seasonal beers made out of malted barley, water and yeast, Reppucci thought there should be seasonal whiskey. He likens the lightly-barrel aged hop-flavored whiskey to an India pale ale.

A 17th-century Influence at Moonlight Meadery

Michael Fairbrother, owner of Moonlight Meadery in Londonderry, New Hampshire, says he found inspiration in part from 17th-century England, and a cookbook called, “The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Kitchen Opened,” that details the food eaten by the wealthy, as well as his own past. “My great-grandmother used to brew during Prohibition, and my parents were home brewers,” Fairbrother said. “What drove me was thinking George Washington and Thomas Jefferson brewed, and if they could do it then, why couldn’t I do it now?”

Mead is made by boiling honey with spring water, adding fruit and/or spices and yeast and letting it ferment before it is aged in a barrel. “I’ve been mead making since 1995 as an amateur, but was really not sure what it was supposed to taste like,” Fairbrother said. “For 13 years, I worked on the taste and flavors.”

Mead became popular as a home brew in New England after the Massachusetts Bay Colony imposed duties on foreign malt, making molasses and honey the more economical choice, Hirsch says. It didn’t catch on in taverns because honey was still expensive, and that ingredient made mead twice as expensive as cider, one-third more expensive than brandy and three times as expensive as rum.

Another part of the appeal was that it was safer to drink than water, which wasn’t sanitized. “If you only had water, you would perish,” Fairbrother said. “If you converted it to mead, you had a much better chance of survival.” Because Fairbrother believes quality ingredients make for quality mead, he uses only true, source-certified, unpasteurized honey, which comes in a wide variety of flavors and colors, bringing variety to the mead. Hirsch includes a recipe from 1764 in her book.

Real McCoy Rum’s Taste Redefines Historical Roots

Hirsch’s book also explores the impact of rum, a spirit that is also the focus for Bailey Pryor, owner of Real McCoy Spirits, based in Mystic, Connecticut. “In the slavery era, the vast majority of rum was made with molasses,” said Pryor. “White refined sugar was more valuable than gold.” That rum, however, was “very rough,” and had methane in it — the product used to make rubbing alcohol — something early distillers didn’t realize they had to remove, he said. “The first thing to come out of the still is methane,” Pryor explained. “You have to know when to remove it, then everything coming out is ethanol, and that’s the good stuff.”

The roughness of rum also mellowed as it was stored in barrels and shipped to New England. Along the trade route from the Barbados, it developed color and caramel-like flavors, Hirsch said. By the mid-1600s, colonists were buying cheap molasses from the French West Indian islands to make their own rum to drink and sell, and New England distilleries thrived in the late 1600s and early 1700s. By the time the British Parliament passed the Molasses Act of 1733, rum made up 80 percent of all exports from the colonies.

The Molasses Act — while largely subverted by the colonists — marked the beginning of the end of rum’s domination in America. The Sugar Act of 1764 reduced the tariffs from the Molasses Act, making molasses more difficult to come by, which slowed production and increased costs. Colonists protested, and tea and newspapers were taxed instead, which ultimately led to the American Revolution.

By the time the war ended, whiskey had overtaken rum as the spirit of choice. Pryor thought unadulterated rum, without artificial flavors or colors, deserved a comeback. He drew his inspiration from the Prohibition-era recipe of the company’s namesake, rum runner William “Bill” McCoy.

“The Real McCoy was the first rum runner — he had a floating liquor store three miles off New York City and was selling unadulterated rum. Every other bootlegger was watering theirs down, adding turpentine, prune juice or water,” Pryor said. “McCoy didn’t do that.” McCoy bought rum from Foursquare Distillery in Barbados, which has been run by the same family since those days. “They agreed to make the exact same rum, same still, same company,” explained Pryor. “For us, it’s a great legacy, a great story.”

History as a Template

“Drinks have become more complex and culinary in the last few years,” Hirsch said. “But at the same time, the trend is moving back to the three ingredient drink.” Using history as a template is an interesting way to find new ideas, no matter which spirit, beer or wine provides the base.

Fairbrother, Reppucci and Pryor each said it took trial and error to hit upon modern blends from old-style inspiration, but for these three thriving enterprises, it’s worth

the effort. As for Hirsch’s recipes, which provide a look at the old, and her experiments with new, trying them at home is worth the effort too.

DRINK RECIPES

Modern Grog

- Ice

- 2 ounces blackstrap rum

- ½ ounce orange liqueur

- 1 teaspoon rosehip simple syrup

- ½ teaspoon fresh-squeeze lime juice

- Dash of orange bitters

- Dash of Chartreuse

In a shaker filled with ice, add rum, orange liqueur, simple syrup, lime juice and bitters. Shake to combine and then strain into a coupe glass. Float Chartreuse on top and serve.

SOL Hopped Negroni

- 2 ounces Sons of Liberty Hop Flavored Whiskey

- 1 ounce sweet vermouth (preferably Antica Formula)

- 1 ounce Aperol

Combine the ingredients in a large mixing glass filled with ice. Stir until glass is very cold, approximately 1 minute. Strain into a chilled coupe or a rocks glass filled with fresh ice. Garnish with a lemon twist.

The Dirty Barbados

- 2 parts Real McCoy Rum

- 1 part ginger-infused simple syrup

- 1 part freshly-squeezed lime juice

- Dash of orange bitters

- Pinch of sea salt

Shake well in cocktail mixer and serve over ice with lime wedge.