By Bob Sample

Just mention the word “retirement,” and most people will conjure up images of warm, sunny locales, hours spent playing golf or relaxing by a pool. Ordinary people, that is. For Connecticut’s Abe Homar, life thus far has been anything but ordinary. At 93, Homar still goes to work every day, as a sales executive for Brescome Barton in North Haven, Conn. He’s been at the top of his profession for a long, long time.

“I’ve never heard of anyone else who at 93, is still working – but what else would I do?” Homar says. “I like my work, the people I work with, and the people I see. I don’t want to ever give that up.” Having a career spanning more than six decades is a huge accomplishment – but what makes it even more remarkable is that, in 1944, Homar wasn’t sure he’d be alive another year, much less another 68 years.

Homar served as an aerial gunner during World War II, during which his plane was shot down. He spent a year and a half as a prisoner of war. Let us qualify that somewhat: as a Jewish prisoner of war.

THE WAR

Back Row, L-R: Sgt. John Hill; T/Sgt. Ro Grandquest, Radio Operator; T/Sgt. Matthew Kryjack; T/Sgt. Abe Homar; T/Sgt. John Guros; Sgt. Omar Sharp

“It was a cold, cold winter and it snowed all the time,” he recalls. “The temperature rarely climbed higher than 10 degrees Fahrenheit. While I was there I caught every disease in the book and constantly battled frostbite – to this day, I still can’t straighten my hands, it was so bad.” In June, camp officials learned that Russian troops had advanced to the next town. “So, they marched us over to the seaport of Memel on the Baltic Sea, where we got onto a coal ship,” he says. “They put about a thousand of us down into the hold of the ship. We slept standing up.”

During the voyage, the Germans would let men go up to the main deck to urinate off the side of the boat. Many jumped overboard and died. Once the ship arrived at its destination, there was more misery as the prisoners were attacked by a gang of Nazi youths. Encouraging them was a German officer whose family had just died in bombing raids.

The prisoners’ next stop was Stalag 4 in Brandenburg state, about 30 miles north of Dresden. The brutality continued, but camaraderie developed among the POWs. Homar taught German classes and helped form a Connecticut Club. In February of 1945, Russian troops again advanced to within a few miles of the camp. The Germans evacuated Stalag 4 – and this time, ordered all the prisoners to march some 500 miles westward.

“We started out in a blizzard,” he says. “We were on the road for 86 days. We slept outdoors. Everybody had pneumonia, diphtheria. We lost a thousand American kids on the march.” Along the route, the prisoners found themselves at yet another POW camp – but this time, all the German guards disappeared and the men began to sense that freedom was at hand.

In the hubbub created by 50,000 people inside a makeshift camp tent, Homar learned that a New York Times reporter was there as well. He and dozens of others sent word home with the reporter that they were alive. Allied troops ferried the remaining POWs to a liberation center in Brussels, where they were deloused. This was the first day of Passover, 1945. The prisoners were transported by ship from France to England, and then boarded a hospital ship, the George Washington, bound for New York. “We sailed into New York Harbor just as the city lights were going on for the night – it was quite a spectacle, and many of us soldiers broke down and cried,” he says.

ON HOME SOIL

Homar wasn’t free to go home just yet. The ex-POWs had to first go to Fort Dix, N.J., for lectures, checkups and ‘R and R.’ From there Homar traveled back to his initial enlistment point, Fort Devens, and then to Hartford’s Rentschler Field to meet up with his family. “When I got home there must have been 200 people at our house,” he says. Homar had weighed about 180 pounds before the War and now weighed a mere 120. Family, friends and neighbors all saw to it that there was plenty for him to eat during the next few weeks.

With several months’ service time left, Homar reported back two weeks later to Atlantic City, N.J. “I had to go to a lot of debriefings – the Army particularly wanted to know what we might know about what the Russians were up to,” he recalls. “They offered me a short assignment to Lake Placid, and I said I’d prefer something warmer – so they sent me to Macon, Georgia, to finish up my service. I was quite happy about that!”

Returning to civilian life, Homar had no worries about employment. It was back to work for his father’s ginger ale company, which Homar purchased. The market changed over

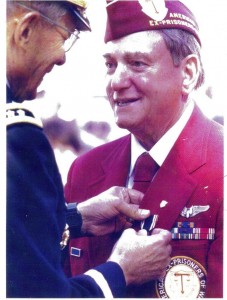

Abe Homar receives honors

the next 20 years. “I was fighting Coca Cola, Pepsi Cola, Seven Up… all the big companies,” he recalls. “They went into my markets, and they wiped me out. So, I sold the business and stayed on as a supervisor.”

Homar began to think about going into liquor sales. His friend had married the daughter of a liquor distributor in Hartford named Max Lewis. Homar’s friend and one of Lewis’s salespeople went to Germany’s Oktoberfest, during which the salesman confided in the friend that he was planning to leave Lewis’s company.

“A few nights after that I got a call from my friend, asking me if I was ready to go into the liquor business,” he says. “I told him I was. That was 47 years ago … and I’m still in the business.” During this time, Homar married and settled down in West Hartford, Connecticut. He and his wife still live in the same house where they raised their two daughters. The daughters in turn grew up, built successful careers, married, and now have grown children of their own.

Homar became active in various veterans groups, received several service awards, and during the Vietnam era became active in POW/MIA groups. He also served as a chaplain for a society of World War II POWs. In addition to a variety of brands he’s distributed for quite some time, he recently became an honorary brand ambassador for Sailor Jerry rum. He’s using his military ties for a good purpose. The rum’s maker donates money to Afghan causes for every case that ships; and having Homar as a brand ambassador makes for great publicity.

KEYS TO SUCCESS

Patience is a key element of success in any endeavor, Homar notes. “In sales, you always have ups and downs,” he says. “Stores go out of business, new stores come along, and some stores merge with others. So you’re losing and gaining people all the time.

Shown at Brescome Barton left to right: Frank Dest, Zone Manager, Don Gabrial, Sales Rep, Callie Bundy, Sales Rep, Frank Coutrone, Sales Rep, Abe Homar, our hero and Sales Representative.

“One thing that I feel is important in sales is to never walk in anywhere empty handed,” he notes. “I give out cookies when I go on sales calls – and now, all of my customers ask for them when they see me come in. I’m the cookie guy.” It certainly helps that the spirits industry constantly tries new things – and they often work. “I never thought flavored vodkas would go over very big,” says Homar, “but people are buying them!

“Our economic climate right now is really, really tough… about as tough as I’ve ever seen it,” Homar adds. “The important thing for new people in sales today is, you’ve got to stick with it and see things through. Things will turn around. Things will get better.”