Ryan Robinson, Director of Education, Brescome Barton and Worldwide Wines.

Vino Mexicano, America’s Oldest Wine Tradition

By Ryan Robinson, Advanced Sommelier-CMS, WSET Diploma and WSET Educator

The first image that comes to mind when thinking about beverage production in Mexico is the vast agave fields used to produce mezcal distillates, such as tequila. Tequila has rapidly risen to stardom in North America, besting whiskey as the second most consumed spirit in the United States. Vodka still reigns supreme as the most consumed and will most likely retain that title for some time.

Most would be surprised to learn that one of the first commercially produced fermented beverages in Mexico was, in fact, not tequila but wine! Long before José Antonio de Cuervo was granted land to grow blue agave in 1758—which eventually led to him receiving the first commercial license to produce tequila in 1795—another industry was already thriving.

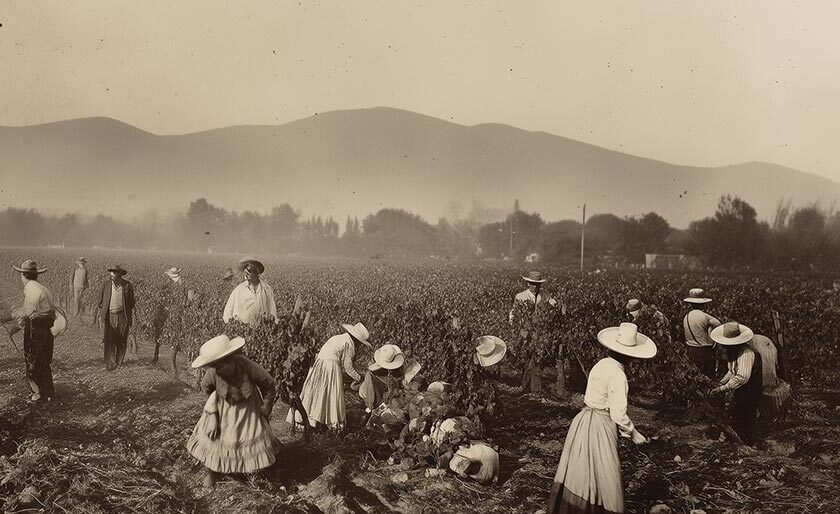

The Spanish conquistadors are credited with introducing Vitis vinifera vines, the grapes that we now commonly associate with modern-quality winemaking, in 1521. Shortly after this introduction, the wine producer Casa Madero was established in Coahuila’s Valle de Parras in 1597. This predates José Antonio de Cuervo by almost 200 years! Casa Madero continues to operate today and retains the status as the oldest winery in the Americas still in operation. To place this in context, the first established winery in what is now known as California didn’t arise until more than 200 years later, known as Jean-Louis Vignes, in 1834.

The Spanish missionaries are recognized as bringing Vitis vinifera vines up the West Coast, as they were intent on establishing missions. This served great importance because in the late 1600s, King Charles II of Spain prohibited wine production in Mexico, yet he allowed for the cultivation of vines and winemaking if it was used for religious purposes. Because of this exception to the ban, Casa Madero was allowed to continue production while the Spanish missionaries continued to travel north, bringing vines and winemaking know-how with them.

Due to King Charles’ ban, commercial winemaking came to a halt and efforts were undertook to restore production in Mexico. Finally, in the 1980s, Mexico saw a resurgence in vine cultivation and wine production. While Mexico does not have a strict Denominación de Origen system like Spain or France, efforts are continually being made to instill a sense of place and origin in Mexican wine production.

As recent as 2015, Valle de Guadalupe was officially recognized as a Geographical Indication (GI) under Mexican law. Efforts continue to establish more GIs to better identify the uniqueness of Mexican wine production areas.

Looking at Mexican wine production today, the majority lies in Baja California, owning a little more than 70% of the country’s total production. Here, similar to California, the Mediterranean climate with the cool Pacific Ocean influence creates an ideal growing scenario. Valle de Guadalupe is located here, along with other prominent subregions such as Valle de Santo Tomás, Valle de Ojos Negros, Valle de San Vicente and Valle de La Grulla. There are additional growing areas throughout mainland Mexico, but Baja California still reigns supreme in total output.

The majority of grape varieties cultivated in Mexico parallel those grown in the north in California with a few outliers. Particularly, Nebbiolo. The king of grape varieties indigenous to Italy’s Piedmont region does well here. Often a finicky grape that prefers its Italian homeland, Nebbiolo makes great expressive red wines. Riesling is another favorite of mine that has been producing some wonderful age-worthy wines in Mexico’s high-altitude areas and even the Spanish Macabeo (also known as Viura in Rioja) and Xarel-lo. The backbone of Spanish Cava is being used to make some unique traditional-method sparkling wines in the Querétaro region.

Mexico is rich with wine-producing history, yet much work needs to be done to bring production numbers and recognition to North American consumers. These wines are familiar yet evocative. They definitely make for an exciting option when searching for something new to explore in a wine shop or restaurant.

Ryan Robinson is the Director of Education for Brescome-Barton Inc., and Worldwide Wines in Connecticut, an Adjunct Professor at the University of New Haven, and is the Principal at SommCentric, a beverage education and consulting agency. He is a member on the USA Wine Tasting Team, representing the United States and the World Wine Tasting Championships and holds the credentials of Advanced Sommelier-CMS; WSET Diploma and WSET Educator in Wine, Sake and Beer; Rioja Wine Educator; VIA Italian Wine Ambassador; Wine Scholar Guild Educator and Italian and Spanish Wine Specialist; and Certified Scotch Whisky.