Jack Kenny, Beer Columnist

By Jack Kenny

A couple of years from now we’ll celebrate the centennial of the start of Prohibition, the great and failed experiment that interrupted and dramatically changed the beverage alcohol industry in the United States. “Celebrate” probably isn’t the right word. We’ll read all about it, of course, but few, if any, will remember it.

People drank during Prohibition, you know. Consuming beer, wine, whiskey, rum, cordials and cocktails was perfectly legal. You just couldn’t make them, import them, distribute them, sell them, or buy them.

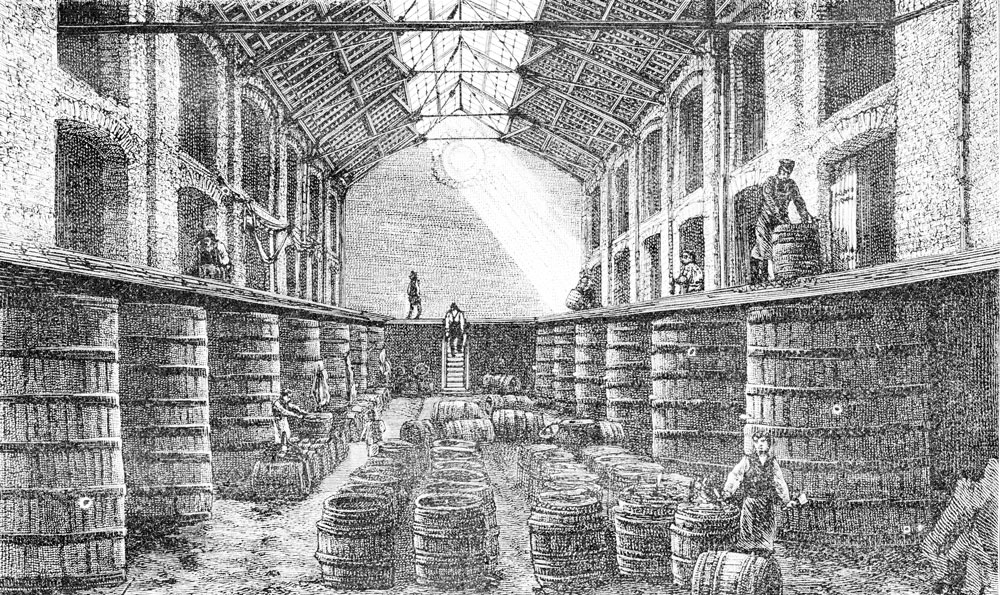

In 1920, when this nonsense took effect, the U.S. had some big brewers. Technology had changed the face of business in the 19th century, and by the time of the Civil War the development of rail travel, the telegraph and mechanical refrigeration allowed small and regional companies to grow and expand. Among these were Pabst, Anheuser-Busch, Stroh’s, Yuengling and Coors. The bigger they got, the more competitive the marketplace became. In its research on Prohibition, Ohio State University reports that “After 1890, beer surpassed distilled spirits as the principal source of beverage alcohol in the American market.”

Competition reached dizzying heights when brewers found a sure-fire way to get their products to the willing lips of customers: the tied house. The big beer companies launched, nurtured, cajoled and muscled saloons to carry their beers exclusively. Most complied. Taverns grew in number, and a town could have one for every 200 people. They were not the kinds of places to which you would escort your mother-in-law. “The typical saloon,” says OSU, “was an affront to ‘respectability’ … Saloon keepers tried to entice new customers, including young men, into their establishments. And they engaged in sideline vices in order to make ends meet – gambling, cock fighting, and prostitution.”

Thus, beer had a significant role in what happened next. Temperance movements, which had been making noise since the mid-1800s or earlier, swelled to the point that they could not be dismissed. The Anti-Saloon League and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, among others, drove the effort to amend the Constitution to prohibit the sale of alcohol.

What, then, was a brewer to do with a factory and an army of laborers who knew pretty much how to do one thing very well? Ah. Never underestimate the depth and breadth of the American entrepreneurial spirit.

Make no mistake: Breweries died by the hundreds. When Prohibition ended in 1933, only a handful remained of the 1,300 that were in business just 13 years earlier. This was as the enemies of strong drink intended. But the brewers who made it through did so by using their wits.

Some went into the dairy business. Yuengling and Anheuser-Busch made ice cream. The former was successful enough to continue that line of goods until 1985. Pabst took advantage of its location in a strong dairy state to enter the cheese business. It aged its product, called Pabst-ett, in the brewery’s ice cellars, and at the end of Prohibition sold the business to Kraft. (Fast forward: As the craft beer business boomed over the past 35 years, many start-ups acquired second-hand dairy equipment because of its similarity to that required for brewing.)

Soft drinks were a popular fallback. Schell’s, Pittsburgh Brewing and Saranac – which still produces a line of sodas – survived by making non-alcoholic carbonated drinks, including near-beer, which contained little or no alcohol. A-B’s Pivo (the word for beer in most Eastern European languages) was one of these. Near-beer, by the way, was popular in the black market when jacked up with distilled spirits.

One Prohibition product directly spun off from beer brewing was malt syrup, the extract of barley produced for baking and cooking. A popular product, it’s likely that this was marketed with a smile, because its main use was as the base ingredient for making beer at home.

Smithsonian magazine reported recently that several brewers converted their operations to the production of dyes for fabrics because of the similarity of production, and because of the shortage of imported dyes following World War I. It turns out that several existing dye companies, noting that similarity, used their plants to make liquor on the sly

People say that Prohibition didn’t slow the consumption of alcohol, but it did. Per capita consumption dropped so far that it didn’t reach pre-prohibition levels until the 1970s.

Jack Kenny has been writing The Beer Column for The Connecticut Beverage Journal since 1995. Write to him: thebeercolumn@gmail.com