Jack Kenny, Beer Columnist

By Jack Kenny

Everyone has good days, bad days and so-so days. Even snails, pine trees and probably rocks. A good day for some could be a bad day for others, though which is which could be confusing (see volcanoes).

It’s very likely that beer – the business and the beverage itself – has enjoyed mostly happy times. It’s the third-most-consumed liquid on earth, behind water and tea. There have been a few dark times, and it’s time to peer into the past at a few of those.

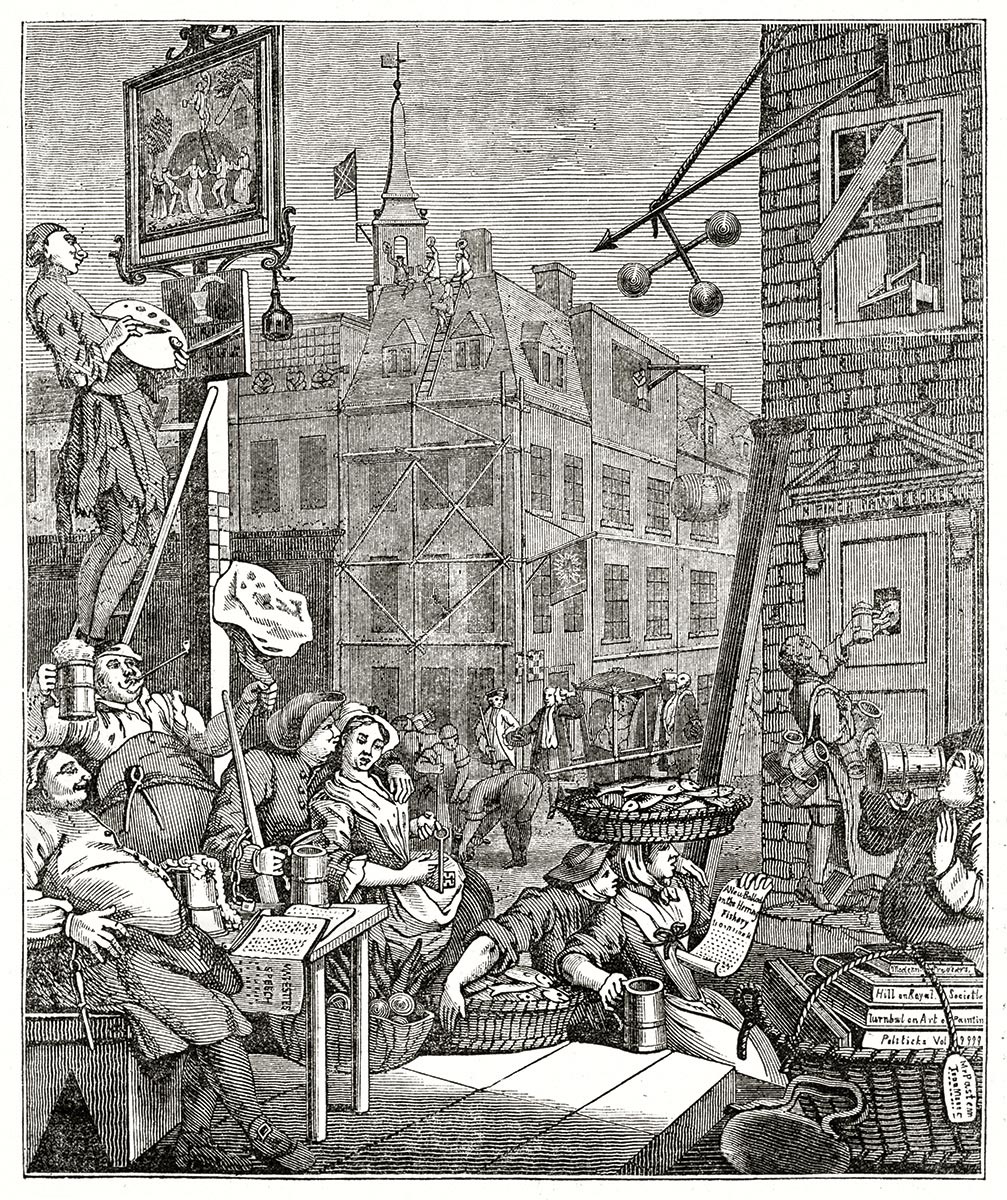

The London Beer Flood surely tops the list of single disastrous events. In October 1814, a 22-foot-tall wooden vat of fermenting porter burst at Meux & Co.’s Horse Shoe Brewery. The eruption destroyed a second vat, and between them more than 540,000 gallons (U.S.) crashed through the brewery’s rear wall and flooded, in powerful waves, the neighboring slum. Eight people died, five of whom were mourners at a funeral. The coroner reported that they all died “casually, accidentally and by misfortune.”

A 15-foot-high wall of porter destroyed two houses. Bricks from the brewery wall were found on the roof of nearby buildings. In the wake of the disaster, rumors abounded that people were collecting as much beer as they could, followed by mass drunkenness and alcohol poisoning. Newspapers reported no such behavior, but the general feeling among Londoners was that such post-flood activity did occur; the English did not look kindly on the Irish poor.

What remained of the area was said to have “a most awful and terrific appearance, equal to that which fire or earthquake may be supposed to occasion.” Some “authorities” charged curious visitors to view it.

This disaster, by the way, pales in comparison to the Great Molasses Flood in Boston in 1919, which killed 21 people and injured 500 when a ruptured metal tank released more than 2 million gallons of the thick sugar liquid into the surrounding area. You’ll have to read about that somewhere else.

The 1900 English Beer Poisoning affected 6,000 people in mid- and northwest Britain, 70 of whom later died. Arsenic was the culprit. After some misdiagnoses, formal investigations revealed more than one source. At first it was thought that low-quality barley was infused with invert sugar, an adjunct that was legal but controversial. The production process contained arsenic, and in this case more than usual. A second cause was the barley itself, which often was dried over coal or coke fires. Arsenic in those heat sources could be transferred to the grain.

Consumption declined in the region after reports of the sickness and deaths. Beer businesses revived after a short time, and ale consumers were back in the pubs within a year.

Consumption declined in the region after reports of the sickness and deaths. Beer businesses revived after a short time, and ale consumers were back in the pubs within a year.

Sometimes drinkers of beer, and spirits as well, were poisoned in the pub. This happened in North America and England in the 1820s, and was said to be a practice of publicans who were, in the words of Charles Dickens, “brewers and beer-sellers of low degree … who do not understand the wholesome policy of selling wholesome beverage.”

The poison came from Cocculus indicus, a plant from Southeast Asia and India whose berry contains a poisonous compound regarded as a stimulant. Its crushed seeds were used traditionally to kill lice and stun fish. It was said to produce nausea, vomiting and stupor. (Nux vomica, the source of strychnine, was also popular.)

Why would a publican serve such a thing? Because Cocculus imparts “giddiness” and heightened pleasure to the drinker – up to a point. The profit came from the practice of adding this venom to low-quality beer, and often adding salt to induce greater thirst.

Sorry, England, but there’s one more unsavory item. Some men sold their wives to other men, usually in pubs, in the 18th and 19th centuries. It’s a jarring revelation, of course, but a couple of details might dampen it. In the vast majority of cases, the women approved of it and sometimes encouraged it. Divorce was nearly impossible then, and when laws changed only the monied class could afford it. And chances were that the woman had already left her husband and was living with the other fellow.

Prices usually were not great: a bit of cash, the occasional dinner or something to drink. The most common payment? A gallon of ale.

Jack Kenny has been writing The Beer Column for The Connecticut Beverage Journal since 1995. Write to him: thebeercolumn@gmail.com.