Amber Jackson, Owner of The Black Leaf Tea and Culture Shop. Jackson moderated the “Addressing Racism in Hospitality” panel discussion held in July.

Industry members share ideas for racial equality in hospitality

By Sara Capozzi and Dana Slone

A group of industry professionals from across the nation met virtually to discuss the issue of racism in the hospitality industry led by a Providence-based cohort. The July 19 panel discussion, led by Amber Jackson, Owner of The Black Leaf Tea and Culture Shop in Providence, invited business owners, chefs, servers, bartenders and others working in hospitality to share stories and give opinions on how to best bring about change, conversations which were fueled by a summer of painful and public race-based violent acts on citizens and following national calls for justice.

With Jackson as moderator on the social media live cast, panelists spoke candidly and personally about the feelings of “otherness,” enduring microaggressions and overt racism to physical violence experienced as Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) workers.

All spoke about a range of topics, from feeling “tokenized” as the only person of color on a team to having to endure the “mental exhaustion” of cultural code-switching, a behavioral strategy for navigating interracial interactions leading to the constant need to “read the room to fit the room” in order to make guests feel “comfortable.” All of these come at a cost of being authentic to one’s identity in order to make accommodations in exchange for their own.

Panel participant and award-winning Providence Bartender Leishla Maldonado.

Panelists shared personal stories demonstrating how the “power structure of racism in hospitality work often has no consequences for problematic behaviors,” said award-winning Providence Bartender Leishla Maldonado, sharing a hurtful work experience from early in her career. Panelist and Bartender Mary Palac said, “You are conditioned to suck it up and not hinder the guest experience.” She highlighted the experience and pain of the “What are you?” question, which she called “so dehumanizing.”

Positive action and affirming one another’s experiences were in the mix, too, as guests ended the session with the group outlining steps to initiate change through their actions, business ownership, community engagement and public policy involvement. Finding solutions for those who say they want a more diverse workplace space is more complex than the surface message suggests because of the systemic, unspoken dynamics between the job seeker, manager or owner of the venue and its clientele. “The problem is that we don’t want to apply because there is something about it that still doesn’t make us feel welcome. If I don’t understand what your establishment is, what it’s serving and the majority of folks in there are white, how are we going to feel comfortable pushing ourselves to fill out that application? I assume that I’m already denied a spot because I don’t look like what you’re putting out. So many restaurants I know want to do this work; I see you and I do appreciate you,” Maldonado said.

“You want to hire more people of color? Go to high schools and put up an ad for internships,” she said. “We’re here in Rhode Island. We’ve got tons of high schools [with] aspiring chefs and owners, and hoteliers. We’ve got one of the best culinary schools in the middle of downtown. Use that as a resource. Work with social groups that help build connections with older students in disinvested areas. Network outside of your social circle. Find spaces that challenge your ideas. Recognize your own exclusivity and break down those walls. This isn’t going to be easy. It’s uncomfortable. But you need to break this cycle. This [work] has already begun, but it’s crucial to keep it going. Professionalism is something we all interpret differently. We need to put leaders in place that understand that there are different ways to approach things.”

A conversation with some of the panelists delves deeper into the ongoing local dialogue.

Michael Silva, Owner of the Providence-based bar pop-up and consulting company BĀS, seeks to broaden the craft cocktail experience, to “educate and inform an underrepresented demographic.”

Michael Silva is a special education teacher at Seekonk High School and also the owner of the Providence-based bar pop-up and consulting company BĀS, which he opened three years ago. Started in his parent’s basement, Silva does pop-up bars in unexpected locations such as diners and factories and also works with restaurants and bars who are “off the beaten path” in Providence.

“Our main goal is to educate and inform an underrepresented demographic in the cocktail industry, specifically in the Providence scene,” Silva said. A Providence native and bartender since 2015, Silva worked as a bartender in New York City before returning to Providence, working at venues including The Dorrance.

“I was the only person in the room who looked like me in front of the bar and behind the bar,” he said. “It was just kind of getting tiring after a while, because I knew this sort of entertaining and dining could be enjoyed by so many other people. That’s how BĀS really got started. There was a void that people don’t really know about or think about, [and I thought] we could do this, in a cooler way and tailor it for people who look like me.”

Silva also began a cocktail kit company, called Mixr, offering curated bar boxes that include everything people need to make their favorite cocktails, including garnishes, tools, syrups and juices, which people can combine with the spirits they have already at home.

To create change in the industry, Silva said, “It starts with infrastructure; putting people of color in powerful positions, and creating infrastructure for people of color to have those positions.” With his companies, he said his goal is “to continue to do the work and continue to market toward brown and Black people and try to make them comfortable in these spaces and provide a space for anybody really … where everybody can feel comfortable and safe and be around these ingredients and these things that they don’t really know about because asking questions is intimidating, learning these things is intimidating but we don’t want it to be intimidating.”

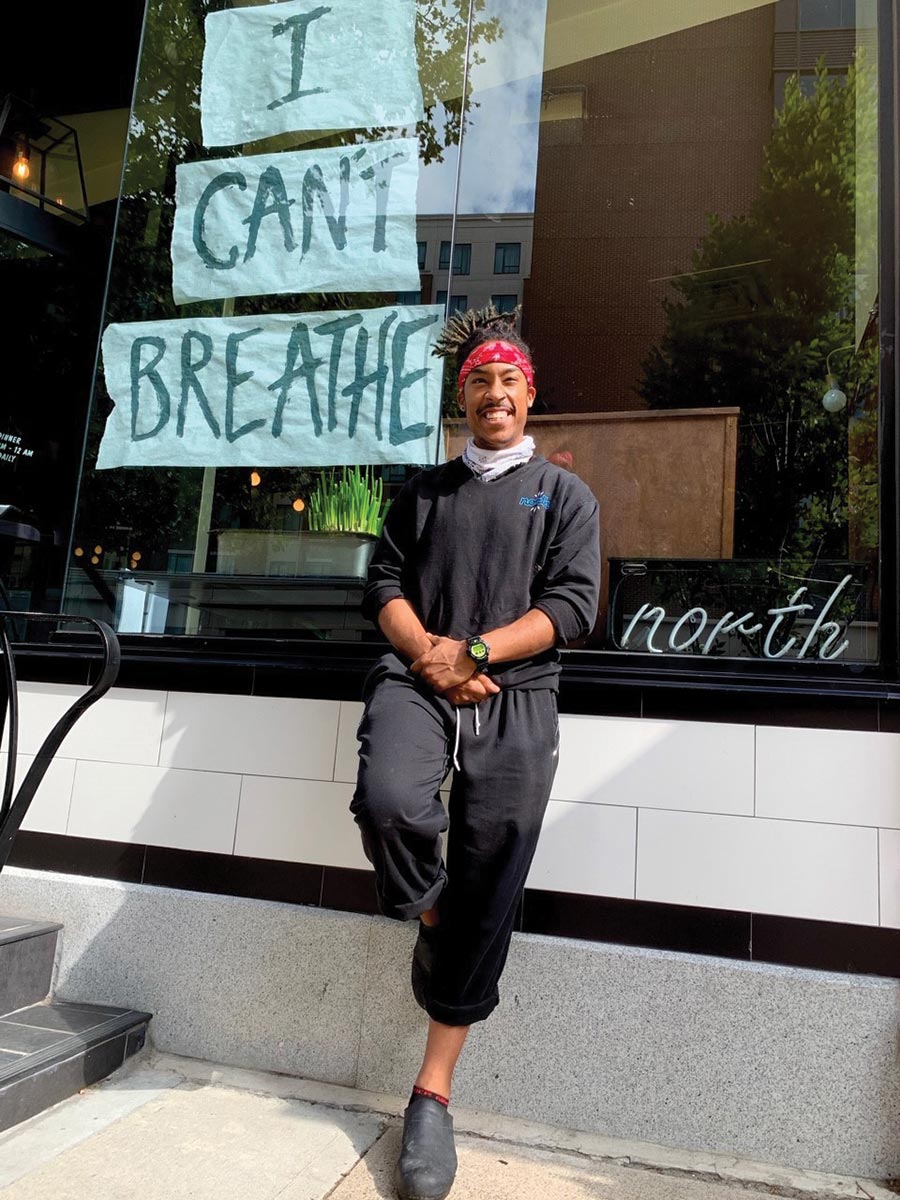

Brandon Puckett, Sous Chef at North restaurant in Providence and Johnson & Wales University graduate, spoke during the panel discussion.

Brandon Puckett, Sous Chef at North Restaurant in Providence, graduated from Johnson & Wales University in 2014. A native of southern New Jersey, Puckett has spent a total of 12 years in the industry.

“When I was younger, I thought the food and beverage industry was one not so much affected by race because of skills and talent,” Puckett said. “So, I thought naively it doesn’t matter what you look like if you can make a good drink or make a nice-looking plate of food. Post culinary school, I quickly learned that wasn’t the case.” After working at a variety of area establishments, Puckett said he has found a home at North restaurant, owned by Chef James Mark.

“As far as company culture goes, it’s been the best I’ve worked for,” Puckett said. “It’s not a tough-guy kitchen, I think that plays a big role because kitchens are often places of misfits and places thriving in homophobia, racist systemic jokes and views. It’s usually home grown in kitchens. Historically speaking, because it didn’t matter what your beliefs were … [it’s about] Can you do this? Can you do that? Can you do it quickly? And I think the industry is changing big time. North’s been a great example for me, a great positive experience for me.

“I’m very fortunate and blessed to work for who I work for and work with, the people I’ve met and relationships built. Not to mention ideals encouraged such as protesting,” Puckett said. “Now that I see that’s possible, I want to try and see if we can re-create that type of culture in other places.”

Puckett has made connections through local efforts such as Jackson’s panel and with other community organizers who are looking to diversify the hospitality industry. Business owners can help be a part of the solution by being “vocal about what it is they believe in,” he said. “I don’t see much negativity about being vocal as a business entity. If people are hurt by that or it makes them feel any type of way … good things come from those tough conversations and feeling uncomfortable and awkward. I think on the grand scale if you lose a side of your customer base, you wouldn’t want them in your establishment anyway. Now is not a time to be complicit for cash.”

Business owners can also be part of the solution by hiring more people of color, and people who may not have the most experience but whose personalities “fit with the culture of the team … The person with the hottest resume might not always be the ideal person to hire. You can teach somebody how to cook, you can’t really teach someone character,” Puckett said.

Owners and operators can help promote fair treatment in the workplace by “making sure that if rules are enforced, they are enforced evenly to everybody,” Puckett added, since “policies can be ambiguous.”

Priscilla Edwards, Owner of The Glow Cafe & Juice Bar, serves up both fresh and healthy foods, as well as community business resources and connections.

Others look to make a difference through the businesses they own. Priscilla Edwards wasn’t on the July panel but is paving her way to helps others. Edwards works as Associate Head Coach of the women’s basketball program at Providence College and also owns and operates The Glow Cafe & Juice Bar on Admiral Street in Providence, which offers fresh-squeezed juices, smoothies and plant-based food in a neighborhood that doesn’t have access to many healthy food options.

“One of the thoughts behind opening The Glow Cafe especially in the the North Providence area was to provide healthy food options in an area that otherwise would be considered a food desert,” Edwards said. “The intention of our location and menu offerings is a response to the lack of healthy options in this neighborhood, it is how we aim to fight systemic discrimination that still exists in America. Food deserts are just one of the ways that BIPOC are targeted. Access to healthy food should not be a privilege, it’s a basic necessity.”

Another goal of Edwards at The Glow Cafe is to help network Black- and minority-owned businesses and business leaders. Opened in 2019, the cafe has hosted workshops and mixers for women and people of color in the community who already are small-business owners or are looking to get started and are in need of connections and resources.

“We found through conversation and collaboration we could help and empower each other. There are unique challenges that exist as women and minority small business owners. Being able to have conversations about these challenges can help us find solutions,” Edwards said.

With social distancing in place due to concerns over COVID-19, The Glow Cafe community is still finding ways to connect and support each other through social media, emails or Zoom calls. As far as what other business owners can do to help encourage more equality in the workplace, Edwards said she believes changing hiring practices and giving Black and brown individuals opportunities to grow is key.

“I think hiring and representation is important. Not just to meet quotas, but because there are talented people in the food and beverage industry that happen to be BIPOC. Again, because of systemic discrimination we don’t always have the same access to get business loans, or open our own storefront, and make it happen,” Edwards said.

She makes an effort to promote other Black- and brown-owned businesses in the area and said others can do the same. “I think there’s a lot of people doing really great things and the quality of the food will rival any business that has a storefront and a huge following – it’s that opportunity to be seen on a wider scale,” Edwards said.

“A lot of things that have been going on racially and social-justice wise have shed new light on Black businesses, which I think is really good. At the same time, I think it’s really unfortunate it took these events for people to realize that there are really good BIPOC businesses in the food industry, that people should support, patronize and care about,” Edwards said. “It says a lot in terms of how far we need to go but it also gives an opportunity for these businesses to survive and thrive … Many of these businesses and brands have amazing stories behind what they’re doing and why they’re doing it.”